"Anyone who hasn't said anything, I've cut them out of my life"

One year into the genocide, Palestinian artist, activist & DJ Nour is done trying to make people care

Nour is a Palestinian artist, activist and DJ who was born and grew up in occupied East Jerusalem. She moved to Canada at 16, then relocated to Mexico City after university and learned to DJ. Before long, she became a resident at Papaya Playa Project in Tulum and began touring internationally. Following the Unity Intifada and Israel’s eleven-day assault on Gaza in 2021 in which at least 256 Palestinians were killed, Nour felt compelled to document the stories of survivors of the original 1948 Nakba. She has visited Nakba survivors in refugee camps in Palestine, Jordan and Lebanon and shares these video interviews in the digital archive she created called the Refugee Chronicles. For years, Nour has also taught creative and DJing workshops for marginalised communities in Berlin, Amman [Jordan], and Palestine. She is Creative Director at the newly opened Palestine House, a cultural embassy in London.

I saw your Instagram story yesterday about being out in London last night and just struggling with trying to act normal while the genocide continues in Gaza and Israel is ramping up its attacks on Lebanon.

It’s been pretty crazy, quite an emotional rollercoaster. Some days you just don't want to get out of bed. This past week has been especially dark.

I can imagine, just coming to terms with the escalation of the war and what that means for Palestinians, and now for those in Lebanon as well. It seems that we’re further than ever from a ceasefire.

Definitely. And we don't know what's going to happen next. We're just waiting, hoping for it to come to an end, but instead, it just continues to get worse.

You’re in London at the moment. Did you go there last December?

I came here last November, and before that I was in Mexico City, I’d been living there for about ten years.

What made you want to head to London?

I was in Palestine on October 7, when everything happened. I was there for the first six weeks of the genocide. I had planned to be doing a project in Palestine in the Balata refugee camp; a creative women’s workshop. Obviously that didn't happen because the war broke out. So everything got cancelled and my apartment in Mexico was rented out because my plan was to be in Palestine until December. By November, you could tell that it wasn't going to get better. All the projects, especially in the camps, got cancelled and I wanted to leave because it was not a nice time being there. I came to London because I have friends here, and when I saw the community and everyone at the protests, it just felt like it was the right place for me to be right now. I have the Palestinian community here and there's a lot happening for Palestine in the creative industries — films, panels, talks. I'm surrounded by community in London.

Just from the photos and video footage I’ve seen online, it does seem like the biggest Palestine protests have been happening in London. Paris gets great turnouts too, but some of the London protests have been huge.

Yeah, I've travelled quite a bit this past year and gone to protests in different places. London's definitely the biggest. There's a big one this Saturday. But I'm not stupid. I know these protests don't do anything. They don’t make a difference, it’s just good for us to scream and yell and chant and be together. I look forward to the protests because I'm going to go out and see other Palestinians and allies and supporters and be in the streets with them and just be sad together.

You don’t think the protests do anything?

I don't know. I mean, it's been a year. I don't see anything being done on the ground. I don't see a difference in policy amongst the corrupt politicians.

What would you like people to do that you’re not seeing enough of already?

People need to stop paying taxes, and really boycott. Take the boycott seriously. Stop paying taxes, go on strike, start fucking with their money. Fuck with their money, then they'll listen to you.

We should probably start boycotting major American companies in the same way we’re boycotting Israeli companies, even if they’re not affiliated with Israel. If their bottom line suffers, they’ll be the ones who can apply meaningful pressure on the government. We can shop at immigrant-owned stores instead.

Definitely. Get away from the franchises, the chains, the Walmarts, the Whole Foods, and just hit up the local mom and pop grocery stores.

I haven't left bed today, by the way. That's how shitty I feel. I wasn't even going to do this interview, but I know we've been trying to do it for a while.

I am so grateful to you for speaking to me at all, and especially right now. I don't blame you at all for being in bed all day. I look at Bisan, and I'm like, how the fuck are you still standing up? I can't even fathom how she keeps going.

And then I start feeling guilty. Like, I'm feeling bad and down and won't leave bed, and then I think about the people in Gaza going through what they're going through. And I’m whining.

No, don’t feel like that. It’s natural you feel this way, it’s your homeland. I was just thinking about Bisan and how she’s managing to keep going in impossible conditions. Even Motaz, who left months ago, you look at him now and the light’s gone out in his eyes. He’s got grey hair that he didn’t have before October 7. I just think about how people are going to try and move through this trauma. The kids who manage to live through this, how will they ever recover?

I don't think they will. They will never be able to live a normal life after what they have witnessed. I was in Bosnia for a conference in June and Samar and Motaz and Belal were there, all photojournalists from Gaza. It was so crazy for me, because I knew that they had just come from there. I've seen the photographs, I know what they have witnessed, and then just to see them and be in their presence…I can't even explain this feeling of sadness and admiration I had for them. I was with them the whole week. We would be together all day at this conference, and then I’d go back to my hotel room every night and start bawling just from the heaviness of it all, and feeling for them. We’d go for dinner and they’d talk, and I’d let them talk but I wouldn't ask them questions about what they’d seen. If they wanted to talk about the experience, they could, but some of the stuff they were saying about what they’d seen was just crazy. Some of those journalists are out now and they’re living in Qatar and they’re the lucky ones, because they got out fairly early, or halfway through. But I was thinking, the ones who are still there now, how are they feeling? Even the ones at the conference who got out, I could see how affected they were. They were very quiet. They didn't want to be around a lot of people, they got anxious if there were too many people around, they wanted it to be just us [Palestinians] together. So I could see that they were not right, and I imagine the ones who are still there today.

What was growing up in Jerusalem like?

Relatively normal, but living under occupation means there would be times where a flare-up would happen and it would be more intense in terms of the occupation presence within the city. At other times it was more okay. But overall you’re surrounded by soldiers, you have to go through a checkpoint just to get to the next town over, and you’re regularly harassed and interrogated by the soldiers on the streets. I have a big family and I have good memories of being with my grandparents and cousins and growing up with them, but it's weird because to me, occupation was normal. We had checkpoints that we had to go through on a daily basis. We had a constant military presence and settlers surrounding us, stealing our homes.

What made you want to move to Canada at 16?

My uncle lived there, and he sponsored me. So I went over there and finished high school in Toronto, and then went to university there.

How did you find going to school there?

I liked it. There were a lot of immigrants in my school, and I was in the ESL [English as a second language] program with the immigrants, and there were other Arabs too. So it was easy for me, I made friends quite quickly. And there are a lot of immigrants in Toronto, especially in the neighbourhood I lived in. So it wasn't like a big difference in demographics when I moved there. My uncle and aunt and cousins had lived there for a long time already, so I was with my family who already knew people and I was integrated into their community.

So you learned English there?

I spoke it before, but just the basics, just enough to get by. I couldn’t have a full conversation or anything like that. But I learned English there and then I went to Ryerson University and studied business marketing. My work now has nothing to do with my degree though, everything I do is in the arts.

At what point did you move to Mexico City?

A few years after I graduated. I just went there on vacation actually, and I fell in love with the country, the people and the culture. It very much resembled Palestine in a way — the mannerisms of the people, the smells of the streets. I felt comfortable super quickly, and I made quite a few friends who are still my friends to this day. I was initially just supposed to be there for a year, but I ended up really loving it.

Did you get stuck into the music scene there straight away?

Yeah, definitely. That’s where I got into DJing. I started about a year after I moved to Mexico City. I've always loved music, and I always loved electronic music and loved going out dancing to it. A lot of my friends in Mexico were DJs and I got them to teach me, and it was just very organic. I started opening up for them at random parties, and then I just met the right people. That helped me to get proper gigs and start travelling as a DJ. It wasn't planned, it was almost an accident.

I think you chose the DJ name Nour Palestina from the beginning, right?

I mean, that's always been my name on Instagram, because Nour was taken. I was in Mexico at the time, Palestinian in Spanish is Palestina, that was honestly my thought process when I came up with that and it just kind of stuck. But I've always been a proud Palestinian. Wherever I go, I make sure everyone knows I'm Palestinian.

I’m sure you've encountered that the vast majority of people don't know much about Palestine or the history.

Oh yeah, definitely, in the Western world. In Mexico they're a bit more educated, they're quite aware. And they support us big time. I've never met a Mexican who doesn't support Palestine. As soon as I say I’m Palestinian, they say, ‘oh, Palestina!’

That makes sense, I loved seeing “Palestina Libre!” everywhere when I was there. What about in Canada? Did people respond to you in a certain way?

I was always around immigrants. I grew up amongst them, I spent my high school and college years around them in Canada. So I wasn't really exposed to a lot of white people, to be honest. I gravitated towards the brown people so I didn't feel any type of racism or someone questioning my identity because the people that I surrounded myself with were fully aware of Palestine and the occupation. Obviously travelling throughout the world and meeting other people, you would get the ignorant one who’s like, what's Palestine? I don't even waste my breath. Honestly, if you don't know that, I don't want to talk to you. And it's not just because it's my country and you don't know, it's because you're an idiot.

It’s not taught in the Western world. We're not exposed to it in school — we definitely weren’t in Australia, anyway. And we’re often fed a completely different narrative.

Yeah, most of the Western world doesn't know the history of what happened in 1948, and the Nakba. I don't even know what they think. They're just unaware. They don't know the history.

If anything, most of them think that it’s complicated.

Yeah. It's actually why I started my project, the Refugee Chronicles. It was after six Palestinian families were evicted in Sheik Jarrah in 2021 and violence broke out and Israel killed over 260 Palestinians. That was the last big flare up before last October. There have been mini ones in between, but that was a big one. I remember posting about it and getting a lot of ignorant questions and people wanting to know why Israel and Palestine are fighting. I basically realised that no one knows the history. That's when I took it upon myself to start travelling to refugee camps and getting video testimonials of Nakba survivors.

I’ve gone to camps in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan. There are hundreds of refugee camps in Gaza and the West Bank. They were tent cities originally and then they made these houses out of this metal material used for making sheds. Eventually they were able to start building actual concrete houses. The roads in the camps are tiny and there are wires and cables and sewage water everywhere…it’s a horrible situation.

How many camps would you have visited in the past three years?

I’ve gone to about fifty and I’ve interviewed over a hundred people. Some of these people are well into their eighties and are old enough to remember the Nakba when it happened. A lot of them are not even with us anymore. And a lot of the ones I did interview have already passed.

How did you find these people?

I’d have a contact in each camp and they know the community, and they know the people living there. So I’d tell them I’m coming in a few days and I need five elders to speak with, and they’d source them for me. Sometimes I’d meet people and they’d end up not wanting to talk about it. I have to respect that.

And you've done all this pretty much entirely on your own, the filming and interviewing and everything?

Yeah. I mean, other than the camp runners, and I have a guy that edits my video. His name is Ahmad. He’s in Egypt now, he was able to get out of Palestine with his family. But going to the camps and documenting it all, that was on me. I taught myself videography when I started doing that project.

Hearing all their stories would probably be very upsetting for you, but it would also strengthen your resolve to keep going with the project, I imagine.

Definitely, yeah. It would make me sad and angry but it was also a realisation, knowing how important it was that other people hear these stories.

I think you're planning to turn them into a documentary?

No, I'm building a digital archive to host them all. There are too many to make a documentary.

There should be a permanent Palestine museum where this work can be hosted.

I’ve done a few exhibits and screenings here in London.

Have you been in touch with many of those people in the past year?

No. I mean, there's no way to really use WhatsApp with them. A lot of those people don’t have phones. But I can only imagine what they're going through, seeing the second Nakba taking place.

It’s kind of like the Nakba never really ended. There have been less intense periods but it’s pretty much been continuing this whole time.

Definitely. They’ve been displacing us ever since it started.

Do you still have family there?

Yeah, all my family is still in Jerusalem, or sort of dispersed around Jerusalem, so my mother and father and (sister or brother?) I also have like a hundred cousins that I grew up with, they’re practically my siblings. And I have my grandparents and aunts and uncles there.

I know it would be impossible to get everyone out, but do many of them want to stay?

They would never leave. Never ever. They don’t want to. They won’t.

Watching the world react to the genocide over the past 12 months, in what ways are you positively surprised? And how have you been disappointed in ways that you didn't expect?

I'm disappointed in the fact that a lot of people have not spoken up. I'm not surprised though. We saw in Ukraine what happened. We saw all the love and support for the Ukrainians and for them resisting the invasion of Russia. We saw the support the refugees got, and the positive media attention. When the same thing was happening to Palestine and Syria and Afghanistan, we saw the double standards then. So I wasn't surprised. I just honestly hate people right now, but I'm not surprised. That people could see a genocide and still be confused about what side to be on and still say it's complicated…that surprises me quite a bit. When people are still neutral on the matter, when they don’t even say anything and don't repost stuff and don’t even acknowledge the genocide, that still surprises me.

Have you been playing any DJ gigs in the last year?

It’s been the last thing on my mind. I've done a couple gigs here and there but nothing like the norm. The idea of being in a club or a bar and dancing and enjoying music, I just don’t want to be there.

Is it that it feels impossible to enjoy yourself in those situations, or does it feel inappropriate to do so with everything that’s going on?

It just felt inappropriate, to be honest, it didn’t feel right. And I see the people I used to DJ with and party with and stuff, and none of them have said anything or spoken up, and I don’t want to be associated with any of them. I don't want to be around most people. Basically, anyone who hasn't said anything or who hasn’t been vocal, I've cut them out of my life. I don't want to be around that music scene that I was part of for the last ten years when all of these people are now staying quiet. Fuck them.

When you say that scene, are you talking about a particular location, or among the parties you played at?

I mean, I was part of this scene where the locations were all over. It was winters in Mexico, summers in Europe, and Burning Man. I never really felt a part of that scene, but that’s where I was playing and those were the people who were booking me. I made acquaintances and party friends, but I never actually made good friends in that scene. I remember a lot of times after I’d played my set, I never wanted to hang out and be around them. But they were part of my life for ten years, and I’d see them all over the world at different festivals and gigs. So they were a big part of my life.

To be honest, it’s not a huge surprise to me that these Tulum and Burning Man crowds have been among the most silent of all.

Yeah, it's actually pretty disturbing. And now, just seeing them all partying and living life as normal, posting from Ibiza while there’s a fucking genocide going on. I don't understand it.

What, if anything, has been a source of comfort to you in the past year? Joy is probably pretty thin on the ground, but what has been encouraging you or sustaining you?

Being here in London and being around the Palestinian community, for sure. And being active and supporting other Palestinians and uplifting one another.

Tell me about the work that you're doing at Palestine House in London. Is that something that just started when you moved there?

Yeah, I actually met the owner a few months ago at an event there. It’s a new space, it’s not officially open yet but it’s basically a cultural space and embassy for Palestinians and their supporters. We do different events — panels, trainings, workshops. We have bazaars and musical performances, and I do the programming there. I'm the program manager. I love it. The owners are Palestinian brothers, and it’s always full of Palestinians, and it’s been decorated in a Palestinian way, so it feels like you're in a house in Palestine. It's been good for me mentally to be there. On Sunday I was feeling so down, and I went there for the Palestinian brunch they put on every Sunday. I was going to just stay at home, but spending the afternoon with them made me feel so much better. It’s a safe space for us right now and I'm happy to be a part of it.

Has there been an initiative over the past few months that stands out especially to you?

The other night I organised an event with Isam Elias, who's a pianist in Palestine, and there was a poet from Jerusalem, Shahd Mahnavi, and they did an act together which was really beautiful. Also we've been doing different workshops highlighting the Palestinian culture, like dabke, and we do Arabic expression workshops. This month is busy. We have a bunch of events and a couple of film screenings and some panel discussions. They've all been nice events, they've all had their own effect on me.

How do you feel like your family in Jerusalem is holding up generally?

Khara. Shit. Honestly, I hate that question.

Sorry. I know it's a stupid question.

How are you and how's your family, I hate those questions.

I know, I'm sorry. Like, I know that it’s shit, I know that you're feeling shit. I know the answer to the question already, but I guess I want people to understand what it's like and how shit it is. I want people to feel something and maybe be moved to do something or say something, or start sharing things, and maybe even change their perspective a little bit if they’re not here already.

I get it. But no, we’re not good.

You probably don’t want to talk at all, which is completely fair. We didn’t have to do this today, we don’t have to do this now. I was just hoping your perspective might make people think a bit.

Fuck people. I'm done trying to make people care, to make them feel something. If people don't care and don't feel anything after what they've seen, fuck them. Please write that in capital letters. If you have witnessed the past year and still don't care, FUCK YOU. You’re not people. You’re not human beings.

Do you feel encouraged seeing people who do care? And people in this industry, groups like Ravers for Palestine who have been very active and vocal?

Of course, that's nice. I mean, I'm happy that there are people in the industry doing something and saying something. Am I encouraged? Not really. I mean, we all need to do whatever we need to do to stay sane. And if making Instagram posts makes you feel sane, just do it.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know?

Fuck Israel. You can say that in capital letters. FUCK ISRAEL.

I’m sorry my love, I’m not in the best state. It’s been a rough few days.

I know, and I’m sorry. I completely understand.

It’s 6pm and I got up to have a shower and then I came back to bed. So that's been my day, that’s how I’m feeling.

I know, and this is probably the last thing you felt like doing. Thank you for even doing this. It would have been totally fine if you cancelled.

I don’t like saying I’m going to do something and then not doing it, because it's already been pushed back a bunch of times.

Well, I really appreciate you making the effort, especially when you’re feeling like this. Thank you.

You’re welcome, my love.

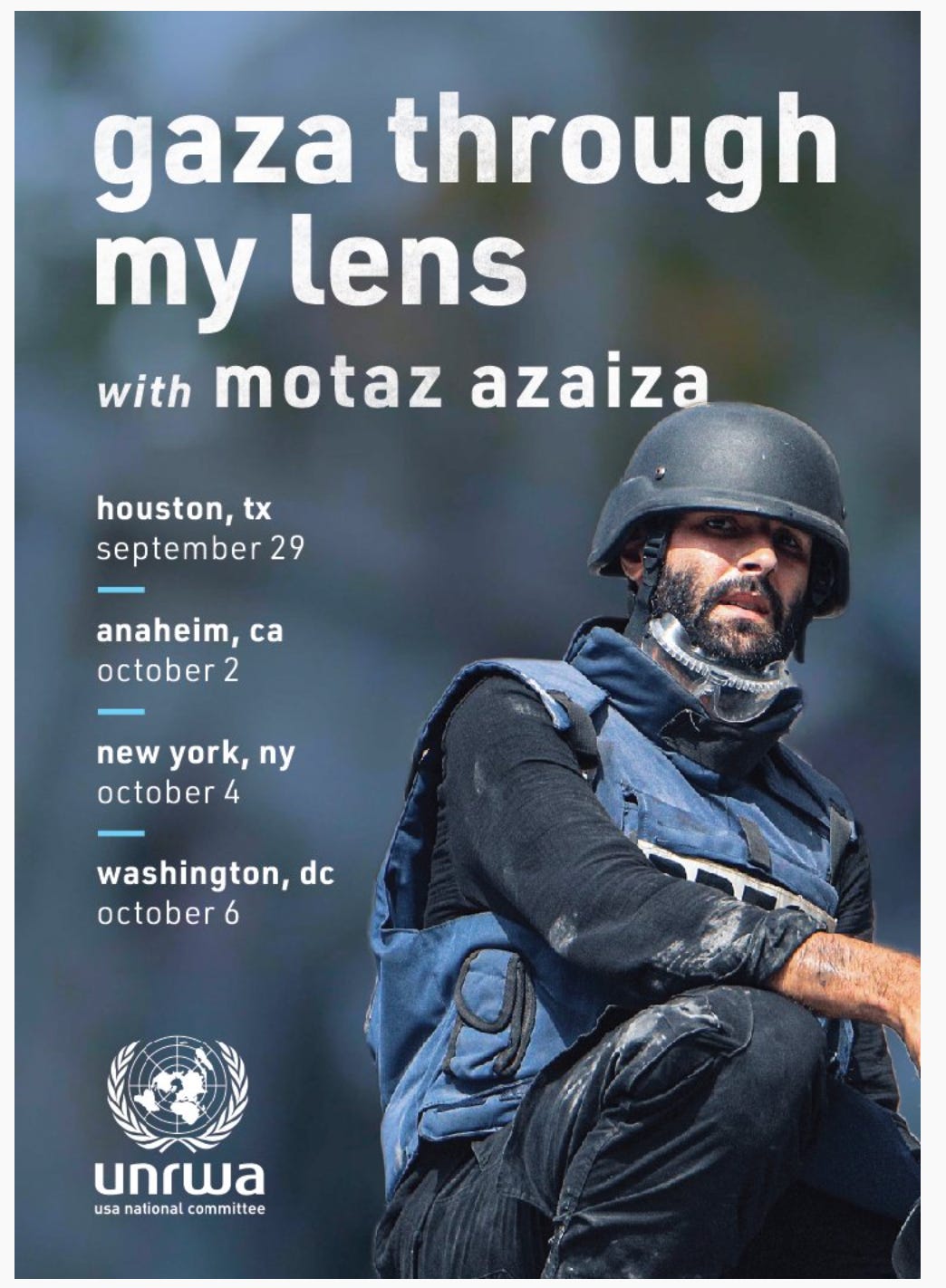

GAZA THROUGH MY LENS WITH MOTAZ AZAIZA. NEW YORK, OCTOBER 4, 2024.

I went to see Palestinian photographer Motaz Azaiza speak in New York last Friday. The venue was much smaller than I expected it to be — I thought he had enough fans here to fill Barclays Center at least. Maybe it was kept intentionally small (around 250 people, perhaps) for safety reasons. The crowd was mostly Arab-American and there were keffiyehs everywhere. Apparently Susan Sarandon had been there in person for the earlier afternoon session (dammit), but we got a video message from Mark Ruffalo in which he criticised the US government for their continued supply of weapons to Israel.

Three of UNWRA USA's senior staff, all of them excellent speakers, introduced the event. The standout was Palestinian Hani Almadhoun, senior director of philanthropy, whose younger brother, sister in law, and four of their children were tragically killed by a bomb in Gaza last November. Almadhoun had visited his family in Gaza just weeks before the genocide began. He has since raised over a million dollars for the Gaza Soup Kitchen founded by his other brother, Mahmoud. His fundraising skills were in full force at the event — he collected tens of thousands of dollars in donations from the crowd, auctioneer style, in around ten minutes. From Hani, we learned that 70% of UNWRA schools in Gaza have been bombed, in spite of signs on the roof in English and Hebrew reading PLEASE DO NOT BOMB THIS SCHOOL. One banana in north Gaza currently costs $12 USD while a carton of eggs costs $110 USD. The soup kitchen needs as many donations as it can get.

Perhaps it's unsurprising, given the amount of talks he's given since he left Gaza on January 23rd, but Motaz is an incredibly polished speaker. I cringed when he said "people are talking about my white hair more than the occupation of my people" — I mentioned that very thing in my interview with Nour — but it's hard not to notice the weight of what he's experienced. He said that 26 of his family members and 18 of his friends had been killed since October 7, 2023, and I can't imagine how many dead bodies he saw in just the first three and a half months of Israel’s assault on Gaza. Hundreds, at least. He cracks jokes and smiles occasionally but the smile never reaches his eyes. I wouldn't expect anything different— in fact I'm surprised he's managed to keep it together at all — but it's clearly something that he sees as his duty, to keep raising awareness about his people and to encourage the rest of us to act through donating, protesting, and continuing to talk about Palestine.

It struck me that in a messed up way, he's the perfect spokesperson for Palestine. A handsome, well-spoken, non-aggressive advocate who risked his life every day to share horrific images of slaughtered and wounded people, he is the type of figure who is easily embraced by Western audiences who demand far too much nicety from their heroes. But I was glad to see he wasn't trying to sugarcoat anything for the audience and spoke frankly about his pain and disappointment, even as his followers on Instagram apologised for their uselessness. "'People said we're sorry, we let you down, we didn't protect you,' and I said yes, thank you for your words because you're right,” he said. “No one protected us. I have all these followers [19 million at the time] and no one protected us."

It's the kind of fame that no one would ever wish upon themselves. Motaz certainly didn't. Prior to October 7 last year, he had already witnessed horrific death and destruction at the hands of Israel, especially during his six months of volunteering for the Palestine Red Crescent Society. But he says he likes to refer to himself as an artist rather than a photographer and at the event, only images of his creative photography were projected onto the big screen. "You already saw the genocide on my [Instagram] account," he explained. His pre-war photos are genuinely gorgeous and weren't easy to capture. “It's hard take colourful pictures in Gaza,” Motaz said.

The photo of Motaz that was used to promote the event was taken by his friend, photojournalist and ambulance volunteer Fouad Abu Khammash. Khammash was killed in January this year when an Israeli tank rolled over the ambulance he was in while trying to help evacuate injured victims from a hospital. Motaz made a point of saying the names of every Palestinian whose story was mentioned throughout the event, dead or alive. Every time he sees that iconic photo of himself, he is reminded of what happened to his friend.

While covering the genocide in Gaza, Motaz slept on the streets most nights so as not to endanger his family. He received many death threats from Israelis daily and worried that his family would be targeted if he went near them. He talked about how crazy fuel prices were in Gaza — at one point it cost him $2300 USD to fill his SUV with diesel, which would only last for a few days.

He was interviewed by Amy Goodman from Democracy Now, which honestly made me feel a little better for asking Nour inherently stupid questions about how Palestinians are feeling at the moment. She inquired about his trauma, and how he's dealing with it. He confessed that after much encouragement from others, he spoke to a psychologist and tried medication, but neither worked. Mental health is not something that's typically treated or spoken about in Gaza, so the concept of therapy and antidepressants was foreign to him. He says the medication made him feel sick and that one session with the psychologist was enough to make him decide it wasn't for him. Still, his survivor's guilt and is clearly overwhelming. He says his stomach hurts all the time, and his social media posts from March and April are unsparing in their honesty. "I am dead inside and will not be able to continue," he wrote. How does someone ever recover from such immense trauma?

"I was so much better before this," he said, referring to his life before October 7. He might be one of Palestine's most famous ambassadors, but "it's not about me, I'm just a symbol," he said. He knows his power as a symbol though, and it impels him to keep going. He spoke fondly of meeting Rashida Tlaib, the only Palestinian American to serve in Congress, and about her bravery in holding up a sign that said “War Criminal” and “Guilty of Genocide” as Benjamin Netanyahu addressed Congress in July. "People are supporting you from here [the US] and people are killing you from here, so you don't know whether to love or hate here," he said.

Motaz gave a talk called “Journalists Under Fire in Gaza” at Columbia in April this year, three weeks before students occupied the university's Hamilton Hall and renamed it Hind's Hall, after the five-year-old girl who was killed in Gaza after calling an ambulance for help. He has a soft spot for Columbia, he says, as the site where the first "real action" was taken in the US against Israel, and joked that he hoped for a scholarship from the university (seriously though why hasn't that happened yet?)

Mid-way through his opening address, Motaz reintroduced himself. "My name is Motaz Azaiza, I'm 25 years old, I'm a genocide survivor,” he said, joking that he deserved a round of applause (it took a moment to recover from that simple yet devastating truth). It marked the second of four standing ovations for Motaz that night. "We are not terrorists, you [Israel] are occupying us, we have the right to resist you," he said to more cheers. As he left the stage, his parting words cut deep. "I don't want the world to keep getting the message that Palestinian life is so easy to lose, and Israeli life is so precious," he said. "Why?"

One year into this horrific genocide, the continued support for Israel from the US and its Western allies perpetuates the idea that only some lives matter. Motaz is begging for us to to prove that notion wrong.